Lower income consumers receive little support to ensure that their hard-earned cash is productively invested in the most energy efficient consumer products that will cut energy bills over their lifetime. While the barriers are well known, they have been stubbornly persistent, and energy burdens remain crushing for far too many. With the rapid advance of digitization and connectivity, the shift to online retail (even for major domestic appliances) and program innovation, "Efficient Shopping for All" is within reach.

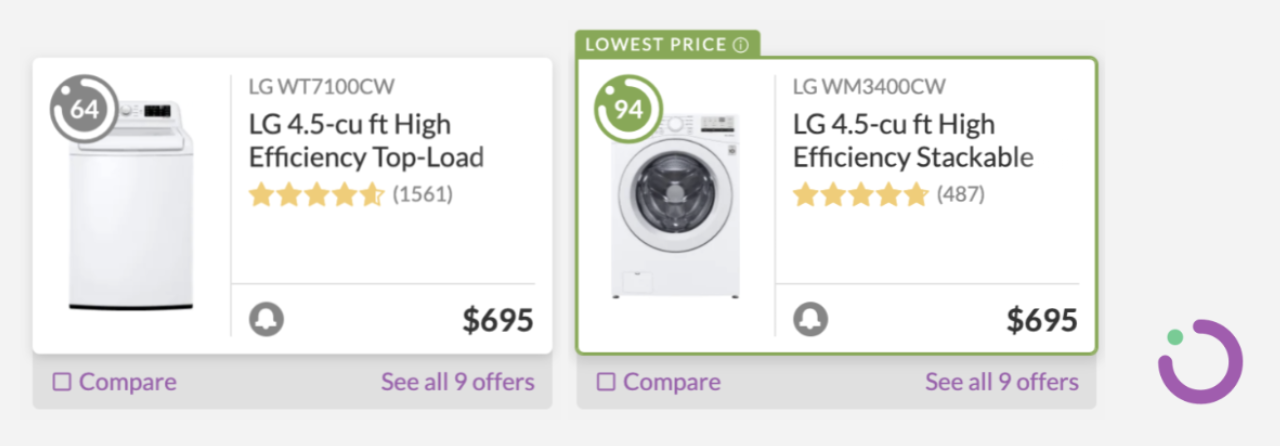

Did you know that front-loading washing machines use significantly less energy and water than top-loaders? Let’s compare these two highly rated LG washer models, both of which you could buy for $695 on February 19th, the day I consulted Enervee’s national Choice Engine platform to find the best deals.

The “high efficiency” top loader on the left uses over twice as much electricity (220 kWh/y) as the front-loader (100 kWh/y) – which is actually the model I have at home, and it works great. While these two models cost the same to buy – and both carry the ENERGY STAR label – the cost of electricity to operate the front-loader over it’s 11-year lifetime is 55% lower than the $377 you would have to pay your energy provider to operate the top loader [1].

In addition, the front loader uses 1,880 gallons less water per year, or a whopping 20,680 gallons over the washer lifetime.

In my town, I’ll be saving $440 in volumetric water and sewer charges and $183 in electric bills at today’s rates over the lifetime of my front-loader washer, compared to the example top loader. My savings of $623 are almost enough to cover the entire $695 purchase price of the washer!

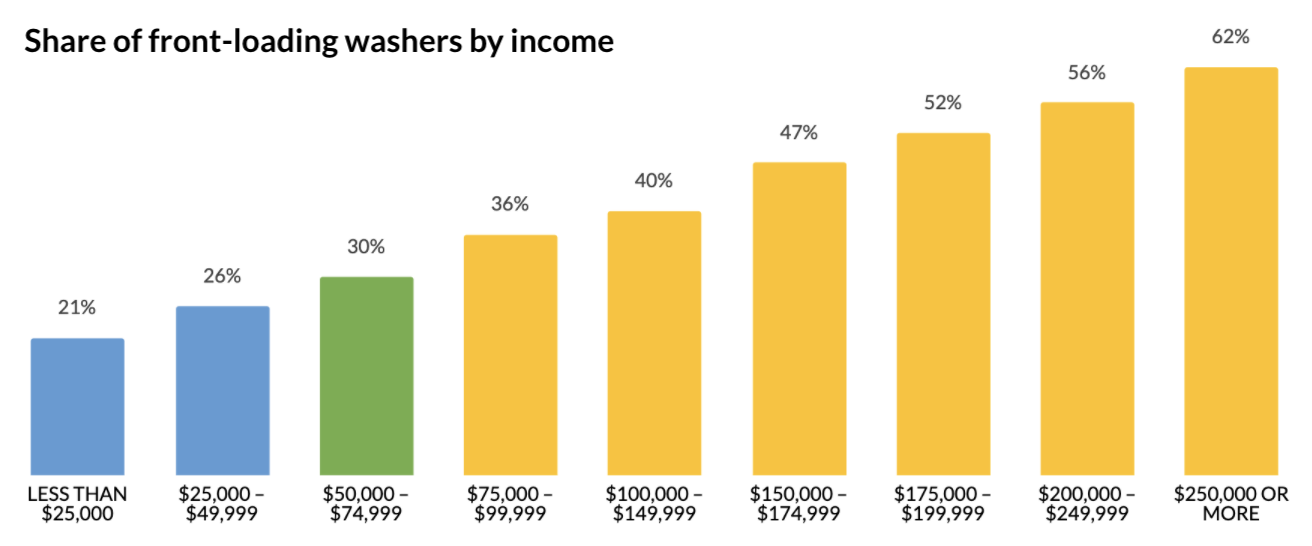

So, why wouldn’t everyone buy the front loader? And why is the share of front loading washing machines directly correlated with household income, as shown in the following chart?

Here are a couple of reasons.

Price premium of new products that rely on cutting edge technology. The cheapest full sized new washer you can find on the market today is just over $600. Only $100 more can get you a super-efficient front-loading washer like the LG model above. But that’s an extra $100 – on top of a major purchase that may not have been planned in advance.

Manufacturers typically introduce the latest technology in higher end models, and they may come with additional material, manufacturing or other costs compared with conventional technologies. Over time, market efficiencies may come into play, as the technologies are adopted in lower-end products at more affordable price points.

So, when a washer fails and needs to be replaced, it’s likely that income-constrained households will focus on price and select models they can best afford, whether they are efficient or not. In fact, our own market research showed that over 40% of people with limited incomes often buy previously owned energy-using products, which are likely even less efficient.

Ability and willingness to pay, given more pressing priorities. There are a number of dimensions at play, including lack of disposable income and more pressing priorities, lack of access to consumer credit, and lack of bandwidth. Millions of Americans are struggling to make ends meet and are having to make wrenching tradeoffs between basics such as keeping the heat and lights on, paying for medication, paying rent, and putting food on the table. Under such circumstances, there is simply no extra $100 that can be spent on an efficient appliance purchase, even if it means lower energy bills in the future.

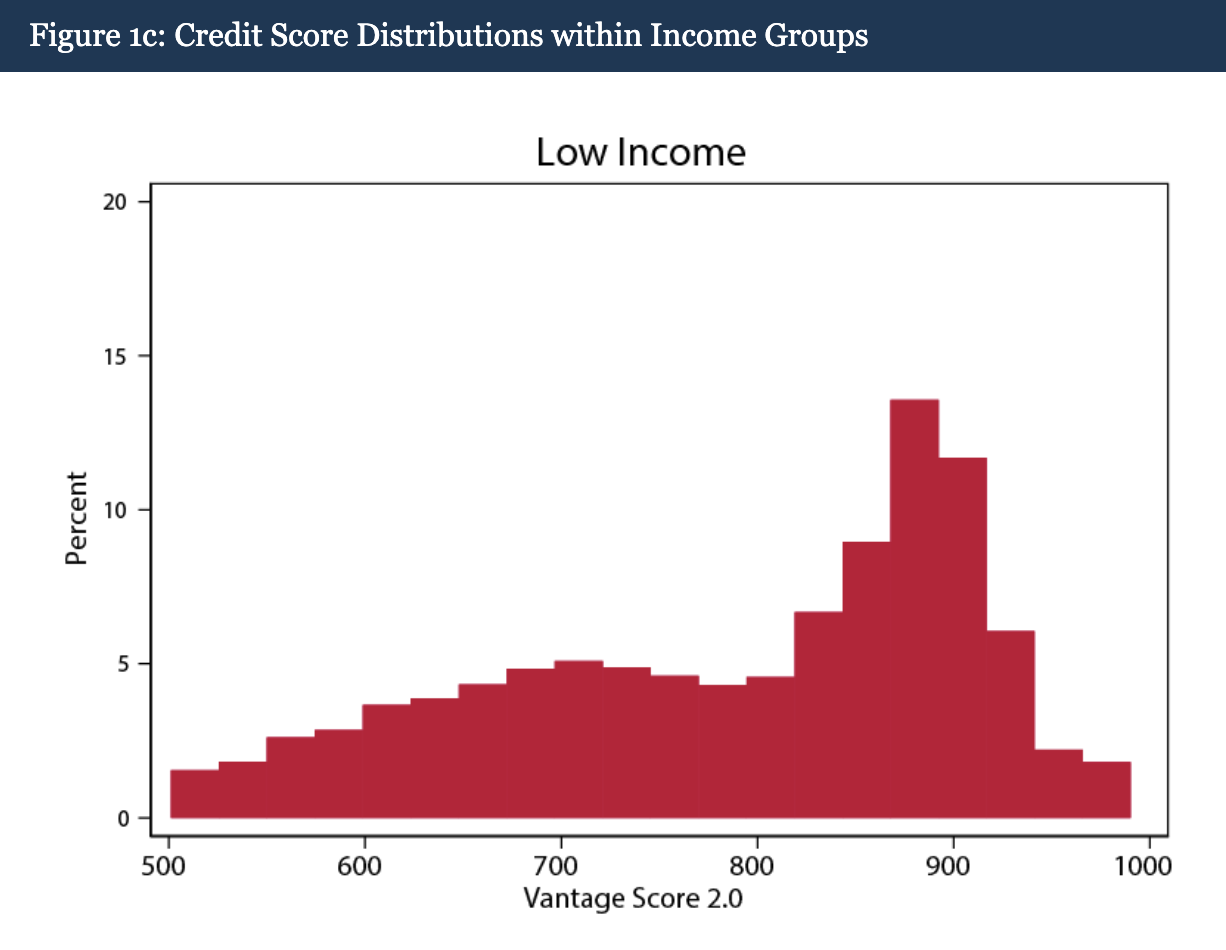

Affordable consumer credit could offer a welcome solution. With the help of green banks, lenders are able to offer term loans at affordable rates (in the single digits) to subprime borrowers with credit scores as low as 580, reaching most people with credit scores, regardless of income. This figure shows the credit score range for the 1/3 of people with the lowest incomes in a study published by the Federal Reserve (Beer, Ionescu & Li, 2018). It's also worth noting another finding from that study, namely that income isn't a strong predictor of credit scores, or vice versa.

Such programs have historically been restricted to home energy upgrades involving contractors, but beginning this month, people making online retail purchases will also have access to this type of consumer credit (stay tuned for the big unveil). This is important, because plug-in appliances and electronics, most of which don't require professional installation, dominate electricity consumption and bills [2].

While inattention plays a large role in under-adoption of energy efficiency in the U.S. (e.g. Allcott & Wozny, 2014), credit market failures may dominate in low-income contexts. A study of clean cookstove adoption in Kenya (Berkouwer & Dean, 2021) showed that access to credit, spreading payments over three months, doubled willingness-to-pay. The study found that two-thirds of the effect of access to credit is driven by the smaller payments due immediately. They also found that, while risk averse consumers have lower adoption, they respond similarly to credit, meaning access to credit can moderate risk aversion.

For those without banking relationships and credit scores, predominantly people of color and with lower incomes, affordable credit is hard, if not impossible, to come by. An inclusive financing approach suited to this segment and proven to be effective is tariffed on-bill financing. Because the loan repayments are tied to the meter, the upgrades that can be financed are limited to items that typically stay with the dwelling when people move. This means that tariffed on-bill and affordable direct-to consumer lending are complementary approaches.

Cognitive load required to consider tradeoffs between purchase price and total cost of ownership. Finally, the market for energy-using consumer products is opaque when it comes to product efficiency, so even if a consumer is able to afford a new appliance purchase, it will take a huge amount of research to choose the most efficient model to meet their needs. While consumers may turn to the ENERGY STAR label to identify efficient products, the side-by-side comparison of the two washer models above illustrates the consumer challenge. In many categories, the market share of ENERGY STAR-certified products is between 40% and 90%, resulting in a wide range in efficiencies among them.

In addition, research has shown that consumers need personalized information on the costs and financial benefits of energy efficiency investments. The FTC Energy Guide label is based on national average electricity rates, which would be highly inaccurate for someone living in Hawaii, Alaska, California, or New England (where rates are significantly higher), and does not provide information on the best retail purchase prices. Research conducted by the Smart Energy Consumer Collaborative found that "consumers want precise cost and savings information" (SECC, 2019) and that this information needs to be applicable to their situation, before they will act. "For under-resourced populations, this personalization may be even more important, because they have less disposable income...” (SECC, 2020).

Enervee’s own published research has shown that when income constrained consumers are provided with a reliable heuristic in the form of a zero to 100 efficiency score, together with personalized bill impact and total cost of ownership information, they choose more efficient products (Arquit Niederberger & Champniss, 2018). These features have proven critical in eliminating barriers to efficient shopping.

Split incentives in rental properties. Building owners of rental properties may not have any direct economic incentive to pay that extra $100 for a high-efficiency front-loader washing machine, if the energy and water bills are paid by – and the resulting bill savings accrue to – the tenants. The 2019 California Residential Appliance Saturation Survey data show that the share of efficient front-loading washers is generally lower for renters than for owners. However, the difference was only 1-2% for households with incomes below $50,000, increasing to as much as 17% for those with incomes between $175,000 and $200,000.

Beyond traditional direct-install programs. Energy efficiency programs targeting low- and moderate-income customers are largely failing to tap into natural equipment replacement cycles and empower consumers to choose the most efficient products to meet their needs. Instead, people are left to spend money on used or inefficient products that perpetuate energy waste and high energy bills. This gaping hole in programming has been called out by customers and other stakeholders – and is beginning to be recognized as an important opportunity to scale the uptake of energy efficient products where they will have the greatest impact on energy burdens.

Some of the key barriers that stand in the way of lower-income consumers buying super-efficient products can be overcome with well-designed programs that:

- Eliminate market and cognitive barriers that generally prevent people from following through on their ambition to choose the most efficient products to meet their needs;

- Eliminate financial barriers, by introducing more affordable and inclusive financing models, combined with instant point-of-sale discounts for people on rate assistance programs;

- Create incentives for manufacturers to develop highly efficient, lower cost models. This can be accomplished in a variety of ways, from technology-forcing standards to bulk procurement strategies.

At Enervee, we've embraced the vision of Efficient Shopping for All and are excited to finally have the opportunity in 2021 to bring these new program designs to those most in need.

------

Notes

[1] These estimates assume 295 loads per year and an average national electricity rate of $0.156/kWh over the product lifetime of 11 years. If you happen to live in a place with higher electric rates, the disparity can be even greater. At an average rate of $0.31/kWh, the front loader would be 28% less costly to operate and save $411 over its lifetime, which is nearly 60% of the purchase price of the washer.

[2] The 2019 California Residential Appliance Saturation Study found that 25% of residential consumption is due to refrigerators and freezers alone.