One of the mantras of behavior change programs is ‘to make it easy’ for those involved to actually change their behavior. At first glance, this makes perfect sense. Want to get people to take more exercise? Give them access to the equipment and facilities. Want to get people to eat more healthily? Then give them access to healthier food (or, make it harder to access unhealthy food, which amounts to the same thing). Frank Sinatra was right: Nice ’n’ easy does it.

The same could also be said for the messaging and communication around behavior change — if the message is easy to grasp and understand, then surely it must then make it easier for us to respond to the message, and start down the road to a modified behavior. There are good arguments as to why this should be the case — we strongly associate the experience we have of thinking about an action, with the action itself. So if we’re reading the instructions for using a new digital camera and we find the experience of reading those instructions easy and straightforward, then we’re likely to think using the camera itself will also be easy and straightforward. This concept of how we think about thinking — our ‘metacognitive experience’ — can be very influential in getting us to follow through with a behavior: if it’s hard to understand, then we typically quickly come to the conclusion it’s also hard to do.

Another way of looking at this quirk of human perception and behavior is fluency and disfluency. Fluency describes when a message is easy to process and understand, and disfluency is when it’s difficult. Fluency and disfluency can be dialed up and down, not only by what is communicated, but how e.g. through different fonts and colors, and even different paper. So here’s an example of reduced fluency:

Now focus on a vital behavior change challenge facing us all today: to use less energy in our daily lives. A key route to do this is by buying products and appliances for our homes that are highly energy efficient. By doing this, a sizable chunk of energy saving is baked-in from the off, thanks to the products’ superior energy performance. If we follow the behavior change mantra (and Frank), then if we’re thinking of buying a new fridge, TV or washing machine, then the explanation of how and why energy efficient purchasing makes sense should also be clear and easy. If we find it tough to process and interpret energy efficiency information (our metacognitive experience), then we’re more likely to believe making an energy efficient choice — and saving energy itself — is also tough.

So nice and easy does it here also, right? Maybe not.

Daniel Kahneman and other leading psychologists talk about our System 1 and System 2 thinking, to categorize how we engage in any thinking effort. System 1 describes our quick thinking mode — picking-up the toothpaste in the supermarket (we quickly recognize the brand colors on the packet). System 2 describes our more deliberative and rational thinking mode — weighing up the features on buying a new car (do I want the leather interior, and in cream or tan?). Importantly, our System 1 mode is always on, and is often all that we rely on to process information and make decisions — if we can get away with not thinking too hard (i.e. engaging our System 2 mode), we will. As Kahneman says: “Thinking is to humans as swimming is to cats. We can do it if we have to, but we’ll do anything to avoid it”.

How do System 1 and System 2 relate to buying energy efficient products? Take a look at these quick mental challenges:

1. A bat and ball cost $1.10. The bat costs one dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

2. If it takes 5 machines 5 minutes to make 5 widgets, how long would it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets?

100 minutes OR 5 minutes

3. In a lake, there is a patch of lily pads. Every day, the patch doubles in size. If it takes 48 days for the patch to cover the entire lake, how long would it take for the patch to cover half of the lake?

24 days OR 47 days

Would it surprise you that the way these puzzles are written heavily influences people’s likelihood to give the right answer? It shouldn’t. A sample of 40 Princeton students were given these three puzzles to solve. Half saw the puzzles in a clear and well-printed font, with the other half seeing them in a small and washed-out font. 90% of those who saw the puzzles in a clear font made at least one mistake in their answers. And of those who saw them in the less legible — or disfluent — font, the mistake rate dropped to 35%. As counterintuitive as this appears, a reduction in cognitive ease leads to a better analysis and interpretation of the data — which meant more right answers.

In other words, the lack of fluency leads us to engage our System 2 thinking mode, which in turn makes us more analytical, and more effectively influenced by rational arguments and detail.

Now think about trying to convince people to buy not just on purchase price, but also on energy efficiency and running costs.

We’re trying to get people to be more analytical and questioning of the normal financial purchasing criteria (price) and to think about a broader concept in terms of cost (total cost of ownership). In other words, to be more analytical and receptive to rational arguments and detail.

With this in mind, making the information as fluent as possible may well be destructive in terms of engaging us in (new) energy saving behaviors, for the simple reason that our System 1 approach carries on as normal, with only the established financial criterion — purchase price — registered as relevant.

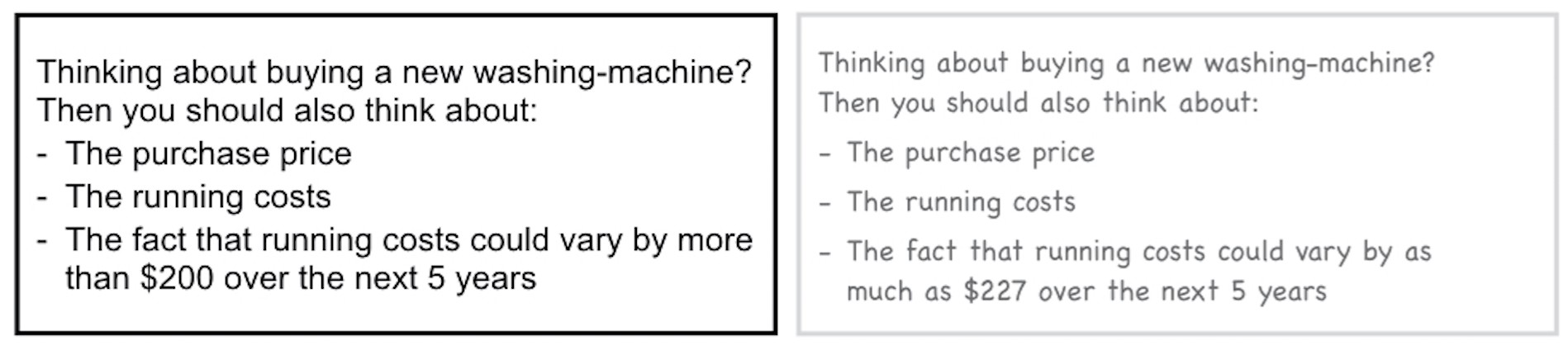

Instead, if we want someone to think meaningfully and to engage on the topic of running costs combined with purchase price, a momentary reduction in metacognitive ease (i.e. making it harder to think about the behavior) — a ‘disfluent’ experience — may be just what we need.

We’re not planning to send the online shopping back to the UX dark-ages. The important word here is momentary: a small injection of disfluency in order to provoke our System 2 mode in order to register and to make the energy efficiency argument salient. We also acknowledge that shopping for appliances most likely also involves our System 2 at specific moments (in fact Kahneman cites comparing two washing machines when considering a purchase as one of the clearest examples of needing to use our System 2). However, we argue there is still the need to make sure the specific message about total cost of ownership and ongoing energy costs (not just purchase price) is registered, processed and understood — and for this we need to think differently about price.

How might we tweak the energy efficiency message to be just a little more disfluent, to better engage? It may be as simple as using a different font, adding decimal places to the data, using distinct color palettes or coining ‘dummy’ acronyms that appear detailed and complex.

From that moment on, we can return to making buying energy efficient products as simple and fluent as possible. With the energy efficiency argument at least established in our consumer mind (we recognize the advantage of buying energy efficient because we’ve now done the math), we’re ready to proceed with a seamless shopping experience, albeit with a crucial change in our perception of what is the right product to buy.

This is just one of the many ideas we’re investigating within Enervee Marketplace. We can do this, thanks to its agile and customizable design, meaning we can experiment and provide richer insights to clients sooner. We’ll be reporting our ‘disfluency’ findings soon. These types of investigations also reinforce our commitment to combine data science, behavioral science and digital marketing to help us all make energy smart buying decisions.

Finally, in case this whole piece feels as if it’s been unfair on Frank Sinatra, well here’s an interesting note to end on: one of the very few songs that he went back and recorded multiple times over his career, was Cole Porter’s ‘I concentrate on you’. Seems Frank also knew the importance of System 2 thinking when it mattered most.

Notes

This paper draws on research undertaken within Enervee and its academic research partners, and on insights from its Marketplace product, which allows consumers to search for energy efficient products, and is deployed with a number of utility companies. For more information on the papers cited, please contact us.