As a Brit working for a US start-up, I’m used to running into the small differences in our own versions of English that can derail or re-route a conversation. All can be going well, with everyone understanding everything, and then the discussion innocently dips into topics such as pavements, boots of cars or people breaking into other peoples’ houses (honestly, to burglarize?) and we’re instantly speaking a different language.

One word and the conversation changes.

In this short paper, we’d like to argue that a single word could also change the conversation we try to have in persuading us as consumers to consume less energy via the products and appliances we have in our home. Just one single word could get us to make more energy smart decisions.

And no, it’s not ‘please’.

First, a little background. Enervee — our company — helps consumers save energy and money, by making it easier to buy more efficient products and appliances. We do this by combining data science, behavioral science and digital marketing to improve the customer journey and the buying experience. One of our principle client groups is utility companies. And with utilities, we’re using our lead product — Marketplace — to help their customers make better buying choices.

Marketplace allows individuals to not only see the typical shopping information (price, features, reviews etc) but also to see up-to-date and personalized energy cost information, i.e. a tailored total cost of ownership, rather than just price. In a market where this information is updated as infrequently as every three years, and is always presented in a generic, average user context, Enervee’s data have the potential to inform and engage consumers around energy usage and its cost.

Another key piece of information in this process — for consumers and utilities — is whether a rebate exists for a specific energy efficient product. We all know what rebates are, and many of us go looking for them in some form when we’re shopping. But as we developed Marketplace, we started to wonder if the concept of the ‘rebate’ was somehow less than efficient.

While the rebate concept from the utility’s perspective is clear — it helps lower the cost of a more expensive, more efficient product — it’s less clear whether the concept is so great from a consumer perspective.

Firstly, there’s the issue that we may be doubtful of a product that has a price reduction (which a rebate in effect creates). Products marked down often give the impression that they’re not selling as well as the retailer or manufacturer had hoped. With appliances and other high-value, difficult-to-install products at home (such as washer-dryers), we want to be buying products that we know are in demand, because they work, and keep on working. So does the concept of a rebate for consumers signal poor performance and poor demand for a product? If the answer is yes, then this is hugely ironic, as energy efficiency rebates exist specifically to make the better product more affordable.

If so, is there an opportunity to remove the potential negative effect of perceiving a poor performance product? Could it be as simple as rephrasing the same financial incentive as an incentive to behave in a certain way, rather than as an incentive to buy a specific product?

In this way, the financial incentive becomes a reward for buying an energy efficient product, rather than a discount on the product.

There’s also the potential issue that the rebate amount is simply dwarfed by cost of the product (think about the typical $50 off a $600 purchase), resulting in us considering the cash back as almost meaningless. This leads to the second — and arguably more compelling — reason to think carefully about reframing the rebate and attaching it to energy saving behavior rather than energy saving products. Support for this comes from Richard Thaler and his research on on the concept of ‘mental accounting’ (2008), alongside research on decision making and how framing can affect our preferences, by Kahneman and Tversky (Prospect Theory, 1979).

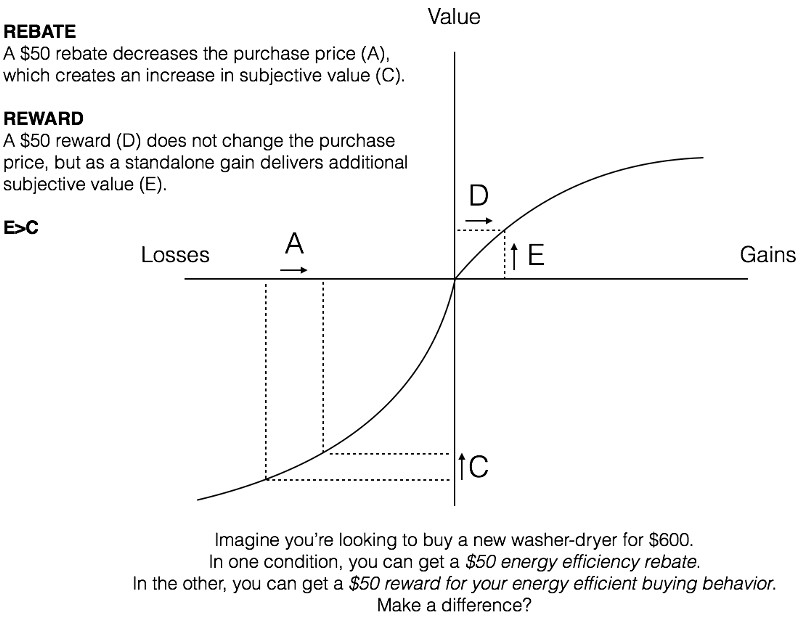

In summary, the concept of mental accounting highlights the fact that it’s sometimes beneficial for the individual to think about cost events separately, as we then potentially account for these events using distinct mental buckets or accounts. The reason we think differently about these mental buckets — shown within Kahnema’s and Tversky’s Prospect Theory — is that the relationship between value and gains or losses is not linear.

More specifically, the relationship between gains and value is convex, whereas the relationship between losses and value is concave. In addition, the curve for losses is steeper than the curve for gains. This latter point explains the sensation that losses hurt more than gains and supports the ‘endowment effect’, whereby things that come into our possession seem to have greater value for us, than before we had them. These areas of research cannot be underestimated in terms of their impact and breadth of application, from paying credit card bills, to making pension savings, or to choosing healthcare insurance packages.

We think there’s also a considerable insight here for energy efficiency rebate programs.

We’ve reproduced the Prospect Theory curve below, which clearly shows the concave/convex relationship either side of perceived gains and losses, as well as the change in steepness of the curve at this anchor point. In what some may see as wholly inappropriate, we’ve also included how a shopper may perceive the purchase of a new washer-dryer in terms of financial costs and associated subjective value. We’ve assumed the washer-dryer costs $600.

We’ve also added a notional $50 incentive for the purchase — both as a rebate (off the cost of the energy efficient purchase) and as a reward (for buying the energy efficient washer-dryer). In both cases, it means the buyer is actually paying $550 for this particular washer-dryer.

Looking at the net value of the transaction, it’s clear that exploiting Thaler’s mental accounting concept could result in consumers perceiving greater overall value from getting a reward than from getting a rebate i.e. the same $50 assigned to a behavior rather than a product provokes splitting the action into two distinct mental accounts. Thaler calls this the ‘silver lining effect’ and occurs specifically when a small gain is segregated from a larger loss. We argue this is exactly the opportunity available with re-thinking the energy efficiency rebate approach.

Results from the frontline

Theory — even when it’s Nobel Prize winning theory — can only go so far. Is there any evidence that such a simple change in language — from “rebate” to “reward” — can change the conversation and modify consumer energy behavior for the better?

Well, the tentative answer is yes.

With one client using Enervee’s Marketplace product, where the term rebate has been swapped out for the term reward, we are seeing the numbers of consumers who opt-in to claim the incentive more than triple. This is a sizable effect.

In the absence of a true experimental design, we acknowledge there may be other factors influencing this outcome, but the fact remains we can increase consumer response rates by a factor of more than three with a simple change in language.

A good definition of a behavioral nudge is an intervention that a) is cheap, b) does not remove choice and c) is effective. The rebate/reward intervention proposed here looks like it meets these criteria: one word changed, consumer engagement tripled, and energy saved.

Some may consider it wholly inappropriate to relate Prospect Theory, mental accounting and their prize-winning authors to buying a washer-dryer. But even White House advisors and Nobel prize winners need to launder their clothes. Talking of which, when it comes to washing clothes, watching tv or keeping a beer cold, here at Enervee we’ve calculated that if we could get just 30% of in-market shoppers in the US alone to buy the most energy efficient product rather than the average (across just five categories), we’d see energy savings of almost 10,000GWh over the next 15 years. Just by buying differently. So we’d argue it’s a pretty valuable application, and is just one of the behavioral science interventions we’re able to develop, refine and deploy via Enervee’s product suite. It reinforces our commitment to combine data science, behavioral science and digital marketing to change the way we buy.

It also reveals what may be an incredibly easy way for utilities to turbo-charge their energy efficiency programs. On this one, my US colleagues and I are in complete agreement on the word to describe this potential outcome.

Awesome.