In this short conceptual paper, we’d like to argue that changing a single — but important — word in consumer communications around energy efficiency could change the conversation we try to have in persuading households to consume less energy via the products and appliances we buy for our homes.

Enervee attempts to help consumers save energy and money, by making it easier to buy more efficient products and appliances. This is done by combining data science, behavioral science and digital marketing within its lead product, Marketplace.

Marketplace allows individuals to not only see the typical shopping information (price, features, reviews etc) but also to see up-to-date and personalized energy cost information, i.e. a tailored total cost of ownership, rather than just price. In a market where this information is updated as infrequently as every three years, and is always presented in a generic, average user context, Enervee’s data have the potential to inform and engage consumers around energy usage and its cost.

Another key piece of information in this process — for consumers and utilities — is whether a rebate exists for a specific energy efficient product. Consumers are well aware of rebates, and many frequently go looking for them in some form when we’re shopping. But in the context of energy efficiency, a natural question arises with respect to the signal such a discount sends to a consumer.

Firstly, there’s the issue that consumers may be doubtful of a product that has a price reduction (which a rebate in effect creates). Products marked down often give the impression that they’re not selling as well as the retailer or manufacturer had hoped. With appliances and other high-value, difficult-to-install products at home (such as washer-dryers), consumers want to be buying products that we know are in demand, because they work, and keep on working. So does the concept of a rebate for consumers signal poor performance and poor demand for a product? If the answer is yes, then this is ironic, as energy efficiency rebates exist specifically to make the better product more affordable.

If so, is there an opportunity to remove the potential negative effect of perceiving a poor performance product? Could it be as simple as rephrasing the same financial incentive as an incentive to behave in a certain way, rather than as an incentive to buy a specific product?

In this way, the financial incentive becomes a reward for buying an energy efficient product, rather than a discount on the product.

There’s also the potential issue that the rebate amount is simply dwarfed by cost of the product (e.g. $50 off a $600 purchase), resulting in the consumer considering the cash amount as almost meaningless. This leads to the second — and arguably more compelling — reason to think carefully about reframing the rebate and attaching it to energy saving behavior rather than energy saving products. Support for this comes from Richard Thaler and his research on on the concept of ‘mental accounting’ (2008), alongside research on decision-making and how framing can affect our preferences, by Kahneman and Tversky (Prospect Theory, 1979).

Prospect Theory, reference points and Mental Accounting

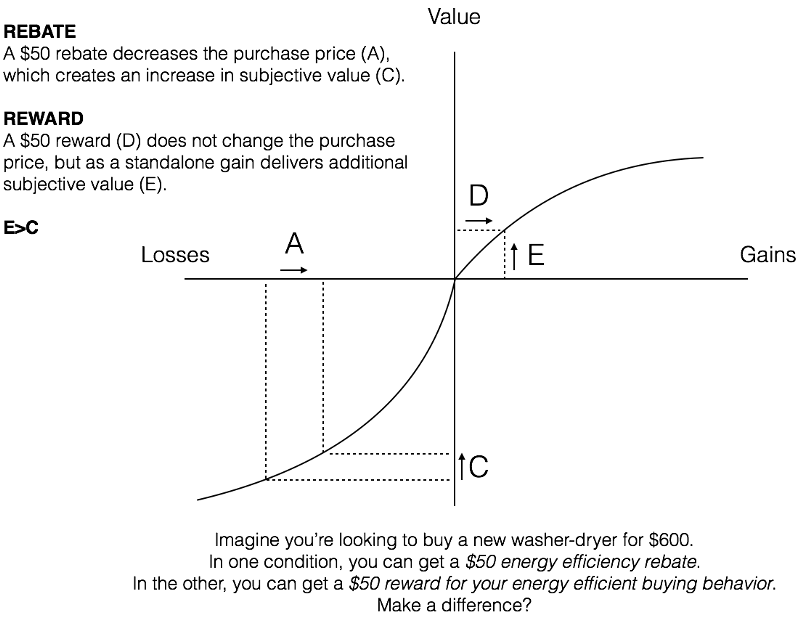

In summary, the concept of mental accounting highlights the fact that it’s sometimes beneficial for the individual to think about cost events separately, as one then potentially accounts for these events using distinct mental buckets or accounts. The reason one thinks differently about these mental buckets — shown within Kahnema’s and Tversky’s Prospect Theory — is that the relationship between value and gains or losses is neither linear no symmetrical.

More specifically, the relationship between gains and value is concave, whereas the relationship between losses and value is convex. In addition, the curve for losses is steeper than the curve for gains. This latter point explains the sensation that, unit for unit, losses hurt more than gains, and sets-up the ‘endowment effect’, whereby things that come into our possession seem to have greater value for us, than before they were ours.

These areas of research cannot be underestimated in terms of their impact and breadth of application, from paying credit card bills, to making pension savings, or to choosing healthcare insurance packages. We think there’s also a considerable insight here for energy efficiency rebate programs.

We’ve reproduced the Prospect Theory curve below, which clearly shows the concave/convex relationship either side of perceived gains and losses, as well as the change in steepness of the curve at this anchor point. We’ve also included how a shopper may perceive the purchase of a new washer-dryer in terms of financial costs and associated subjective value. We’ve assumed the washer-dryer costs $600.

Finally, we’ve also added a notional $50 incentive for the purchase — both as a rebate (off the cost of the energy efficient purchase) and as a reward (for buying the energy efficient washer-dryer). In both cases, it means the buyer is actually paying $550 for this particular washer-dryer.

Looking at the net value of the transaction, it’s clear that consumers may perceive greater overall value from getting a reward than from getting a rebate i.e. the same $50 assigned to a behavior rather than a product provokes splitting the action into two distinct mental accounts. Thaler calls this the ‘silver lining effect’, and it occurs specifically when a small gain is segregated from a larger loss. We propose this is exactly the opportunity available with re-thinking the energy efficiency rebate approach.

Tentative evidence of the effect in the field

The discussion above is based solely on a conceptualization of the effect. That said, mental accounting and reference point effects have been shown to exert considerable influence in real decision contexts and are frequently leveraged by marketers for their companies’ gains. A good example is credit card companies successfully lobbying gas stations to show lower cash prices as a discount for drivers, rather than having credit card prices presented as a premium — the subjective value gain to the cash-paying driver from the discount is less than the subjective value loss to the credit-card using driver of paying a premium. Closer to home, there is also a result that lends tentative support to this conceptualiza-tion for energy efficiency rebates, through one of Enervee’s clients choosing to convert a proportion of the energy efficiency rebate for a product into an energy saving kit for the same value. This has resulted in a dramatic upswing in efficient product purchases carrying the energy saving kit (300%). Providing such a kit could certainly be seen as segregating the effects in line with Thaler’s ‘silver lining’ argument. However, we also acknowledge other possible explanations for this result, such as crowding-in effects, whereby a non-financial incentive (the kit) triggers a different consumer response to the request. We will discuss these non-financial incentive effects in a follow-up paper, but for now remain extremely confident that mental accounting effects offer considerable — and easily captured — benefits for utilities looking to engage households in more efficient purchasing behavior.