When it comes to energy efficient behavior, I’d argue 15% is really pretty sizeable.

Getting us all to think about making more energy efficient product purchases is tough. Even the most determined of us seem to find it hard to make the most energy efficient choices when buying or replacing appliances in our home. A large part of that failure may well be down to us not being able to get the best information at the time we are buying.

But if we’re honest, it’s more than that.

The ugly truth is that it’s likely energy efficiency is simply not top of mind when we’re making the decision — price, availability, reviews are all more pressing attributes that we consider. What’s more, it’s likely energy efficiency will never be able to compete with these more immediate, tangible attributes in a purchase decision.

However, it may be the case that simply asking consumers to think about their purchase within an energy efficiency environment could result in more energy efficient choices. That is to say, energy efficiency could compete with these more immediate product attributes by providing the context within which to make a purchasing decision.

This may be the case due to a mechanism called ‘precommitment’ that Richard Thaler and others have explored in the context of pensions contributions and other ‘difficult-to-get’ behaviors (Thaler & Benartzi, 2004). Precommitment recognizes that people who commit to something in the future are more likely to follow through and honor that commitment, than were they asked to commit in the moment. Precommitment has been studied in the context of charitable giving and volunteering, showing people engage in both of those behaviors more when they’ve made a commitment in the recent past to the behavior.

Why would this be the case? When we’re asked to do something that is ‘right’ (e.g. eat more healthily, take more exercise, donate money or time) we’re confronted with two effects. First, there’s the elation from agreeing to do something that is ‘good’. But there there’s also the realization that this will likely ‘cost’ us somehow (e.g. taste, time, money, effort or enjoyment). With these conflicting responses to the request, it’s no wonder some people land on the side of ‘yes’ but many land firmly on the side of ‘no’.

However, if we’re asked to ‘precommit’ to doing something right — i.e. commit now, but do it later — then we receive the initial positive hit from committing to the action, but without any of the associated ‘cost’, resulting in us typically agreeing to the request (as there’s no conflict). Then, when the time comes to actually carry out the behavior, whilst we then anticipate the ‘cost’ of this action, it’s outweighed by our need for our behaviors to be consistent with our attitudes. So we engage in the behavior.

If this is a feasible explanation of the precommitment effect, then the argument says if you were to bring consumers into a buying environment that has an underlying commitment to buy more energy efficient products, we could expect to see an overall improvement in energy efficient purchases. This would happen as consumers would, in effect, ‘precommit’ to the idea of buying more energy efficient products by visiting the site (it’s a good thing to do, and there’s no perception of cost at this moment) and then remain consistent with this pro-energy attitude when finally choosing a product.

Precommitting to buying more energy efficient products

At Enervee, we have a product called Marketplace. Marketplace offers consumers the opportunity to browse electrical products and appliances, with the important addition of energy efficiency scores for every product. There’s more to it than that, but for you and me as consumers, Marketplace is positioned as an energy-smart buying site, and is typically housed within the energy efficiency and energy saving pages of our utility company. So when customers visit the site to browse for products, energy efficiency provides the context within which consumers consider their options and, importantly, consumers ‘opt-in’ to this proposition when browsing on the site.

If the idea of precommitment is valid, then we would expect to see some effect in terms of the site itself (and its focus on energy efficiency) securing an implicit precommitment from consumers who use the site. This effect would be seen through a trend in making more energy efficient purchases.

The 15% Effect

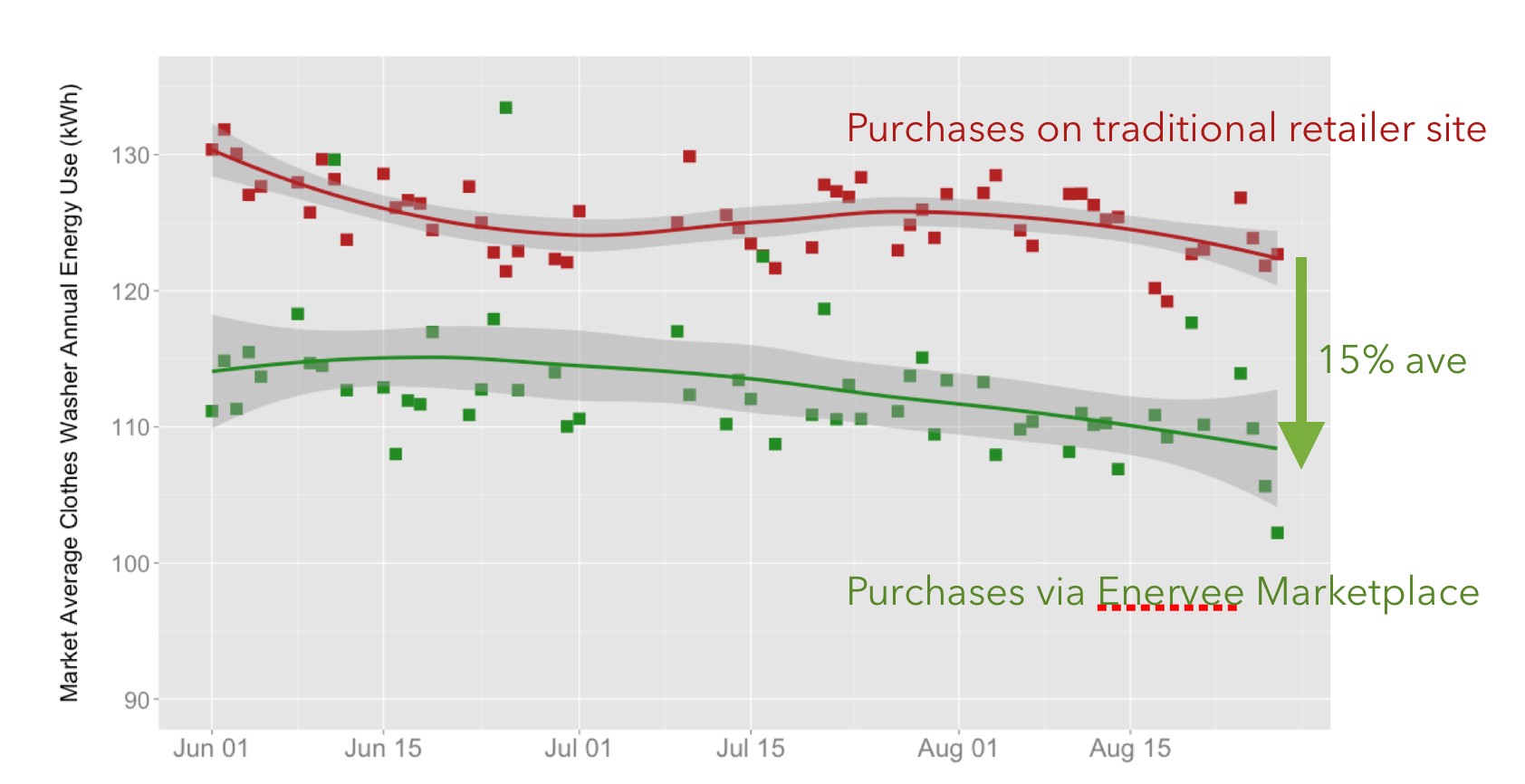

This is the case. Looking at data over a period in 2015 with Enervee Marketplace deployed with a leading US utility company, when starting their buying journey on the site, consumers buy products that are, on average, 15% more energy efficient than comparable products bought via typical online retailers.

For obvious reasons, we’re calling this ‘The 15% Effect’. And we think it’s quite significant.

Several things are interesting about ‘The 15% Effect’ and should be explored further. First, visitors to the site were just regular in-market appliance shoppers, so there was no particular predisposition to favor more energy efficient products.

Second, within Marketplace, consumers cannot actual buy the product, but have to then go on to a retailer site (they can choose from many). This implies the precommitment effect maintains even when they leave the initial site that has secured the implicit precommitment to energy efficiency.

Finally, the only aspects of Enervee Marketplace that lead to this possible implicit precommitment are the general language around energy efficiency, the site’s location within the energy efficiency area of the utility, and the use of an energy efficiency score graphic next to each product being viewed. So it seems the mechanism to secure this precommitment (and actual energy saving buying behavior) need not be heavy handed and obvious, but can be discrete and subtle. It also doesn’t restrict consumer choice (all the same appliances can be seen), and it’s cheap to implement. These factors combine to define what can be seen as an effective ‘nudge’. The importance in nudging us all toward making more energy efficient choices cannot be underplayed. We — as consumers — have an immense responsibility to moderate our behavior.

But the elegance of this particular route is the behavior we’re attempting to moderate is the purchase behavior; that by simply buying the better machine, energy saving occurs. We don’t claim for one second this can take the place of ongoing behavior change, but it is a clear opportunity to deliver huge savings independently of ongoing behavior.