At Enervee, we’ve run quite a few experiments now to better understand how and when our unique data-points can influence consumers to buy more energy efficient products. We’ve focused these experiments — in the main — on the effect of the Enervee Score. As a quick introduction, the Enervee Score is unique to our product, Marketplace, and shows a 0–100 relative energy efficiency score for every product in a category. It’s our way of giving the consumer a datapoint that’s both granular (0–100) and dynamic (it’s updated every day) but that’s also intuitive and easy to understand (just aim for 100). We also design it in such a way that it respects key aspects of a decision that’s already been made: if you’re looking for a 55" TV, it’s not right to try and steer you towards a 40" TV which uses less energy. Instead, the Enervee Score allows you to see which 55" TV is the most efficient.

Back to the studies. So far, everything points to the Enervee Score working effectively to lead people to make more efficient choices. We’ve seen this across different product categories — from more functional white goods such as washing machines, to more exciting goods such as TVs. In other words, products that may prompt the use of different choice models when we’re deciding (from ‘affect-driven’, to ‘attitude-driven’, to ‘attribute-driven’). Regardless of the choice model, the Enervee Score seems to kick-in and make a positive difference. We’ve also looked at different consumer groups — from regular consumers, to low income consumers. We’ve also looked at self-reporting Republican and Democrat consumers to see if there’s an effect. Again, across all of these variables, we see the Enervee Score work drive us toward more efficient purchases.

It doesn’t seem to matter what the product category is, or the consumer type — the Enervee Score moves us. And in a good way.

If it’s not who or what you buy, could it be about when..?

But one variable we’ve not yet explored, is a crucial one in terms of the buying experience and the decision making model used. It isn’t to do with the product, or the type of consumer. It’s to do with the reason we’re buying the product in the first place.

We’ve recognised for a while that we could segment users of Marketplace based on their reason for buying a product that features on Marketplace. If we think about buying a washing machine, for example, we could be in the market to get one because we’re remodelling our home and that includes the laundry room. Or, it could be because our current machine packed up last night, and we need to get a new one to ensure the kids hit school on Monday in something that’s (vaguely) clean and (loosely) ironed.

It’s not a big stretch to imagine that these two buying contexts — planned and distressed — may have a significant influence on what factors are involved in the decision making process, including how much the energy efficiency of the product is factored into that decision process.

A planned purchase — which is likely a more deliberative and attribute-driven decision process — we’d to call a ‘slow buy’. And a distressed purchase — when the product needs to be here now and just get the job done — we’d like to call a ‘fast buy’. Yes, we know, it’s an awful (mis) use of Daniel Kahneman’s seminal text on decision making styles, and all for the purposes of arguing for better appliance purchases for our homes. But let’s be honest, it’s also not the first time we’ve blatantly used world-class research to make a case for this behavior — we’ve discussed Richard Thaler’s choice of washing machine before now. We’ve said it before and we’ll say it again — no-one ever won a Nobel Prize with a dirty shirt.

Can the Enervee lead people to buy better, regardless of why they’re buying?

We recognise that buying context could make all the difference in terms of factoring in energy efficiency as a valid attribute in the decision making process. And we recognise that energy efficiency can seem like an abstract, distant concept at best, and that when under pressure to make a quick decision — to get the clothes clean NOW, for example — those distant and abstract notions can quickly take a back seat. But then again, Enervee is a little different — we try to make energy efficiency less abstract and less distant, by making it relevant, personal and instant.

With this in mind, we went into the latest experiments confident that we’d see the same effects; than even when people have to buy now, they can still be encouraged to think about the future.

The design

Once again, we returned to our washing machine study, which involves a customised version of Marketplace where respondents are asked to make a choice from a number of genuine products (with genuine product data).

And once again, we manipulated key aspects of the normal Enervee experience in order to better understand how these influence choices: the Enervee Score, and the Energy Savings (projected specific product savings over a fixed period). In addition, we also manipulated the cover story for the study. This time, we introduced respondents to the study with the premise that they were either being asked to select a new washing machine based on a wider project to remodel their home (the ‘slow buy’) or that they were having to replace the machine in a hurry because their current machine had just stopped working (the ‘fast buy’). Respondents across both of these conditions were then exposed to the exact same manipulations in terms of Enervee Score and Energy Savings information.

Overall, then this gave us a 3-way factorial design: Buying Context (Fast, Slow) x Enervee Score (Yes, No) x Energy Savings (Yes, No). Cell size was 50 , which, across the eight permutations, resulted in a final sample of N=207.

Does a distressed washing machine purchase send energy efficiency into a spin?

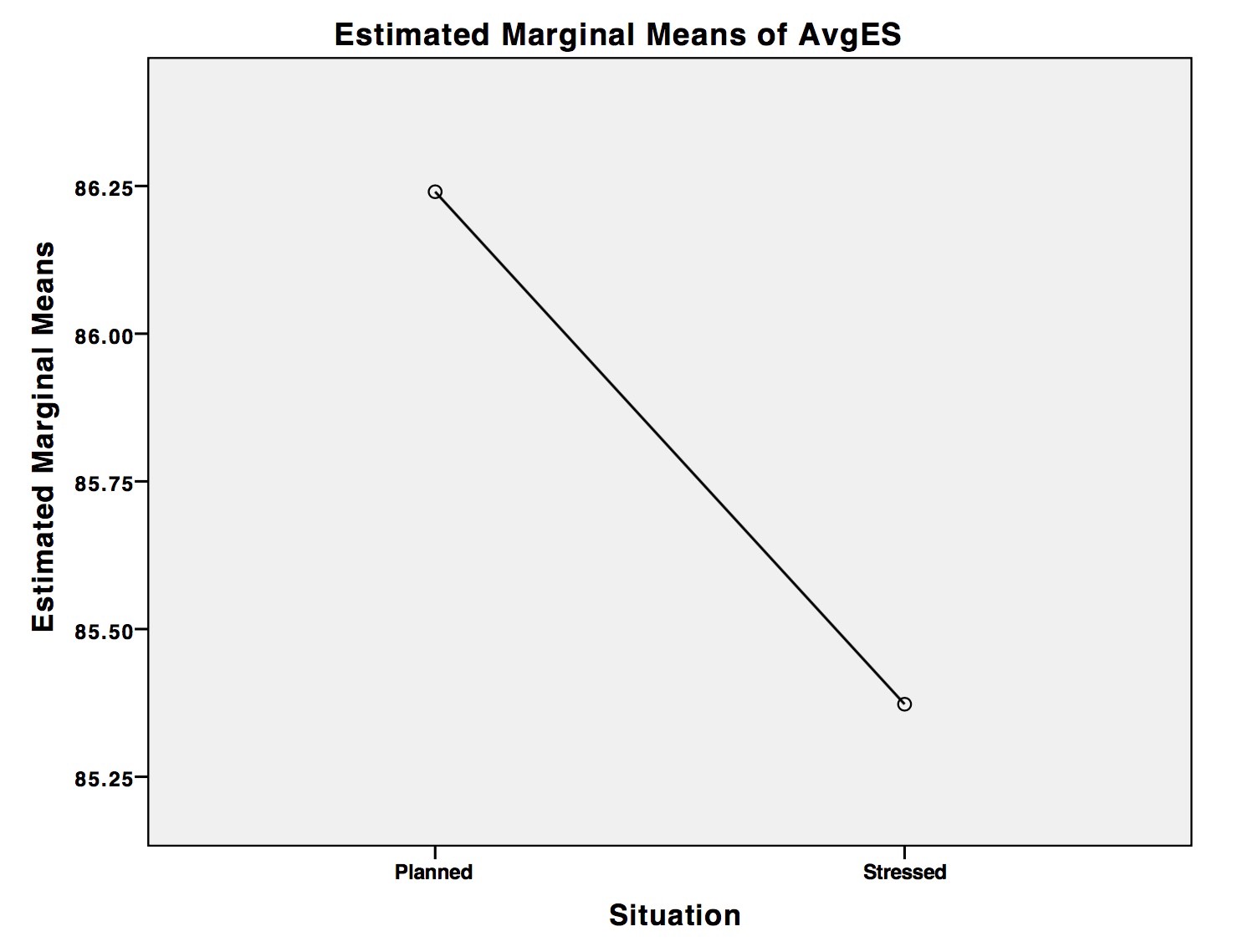

In terms of results, the first thing we see is that people make significantly less efficient choices overall when they’re having to buy in a hurry. In other words, a distressed, fast buy results in lower energy efficiency. When we’ve time to plan and buy slowly, the top three washing machines selected had an average Enervee Score of 86.25, compared to 85.35 when in distressed mode (F=6.02, p<.05). See Figure 1.

This is not surprising — as outlined earlier, it’s very likely that when under pressure to make a purchase, that abstract energy efficiency argument struggles to get any purchase in our decision making. Literally, the future gets marginalised by the here and now.

But what about the Enervee Score and the Energy Savings? Did they work?

Yes, they worked.

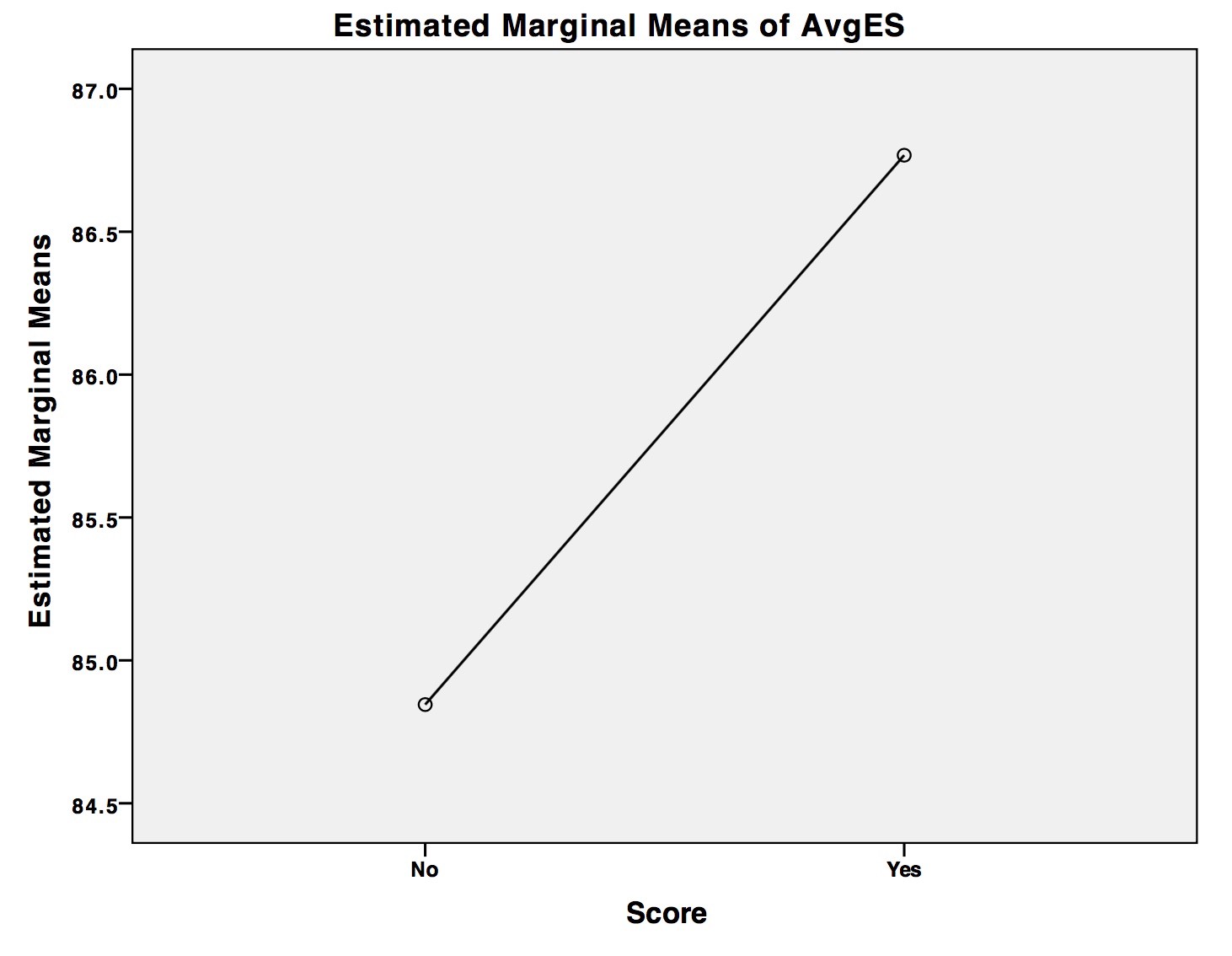

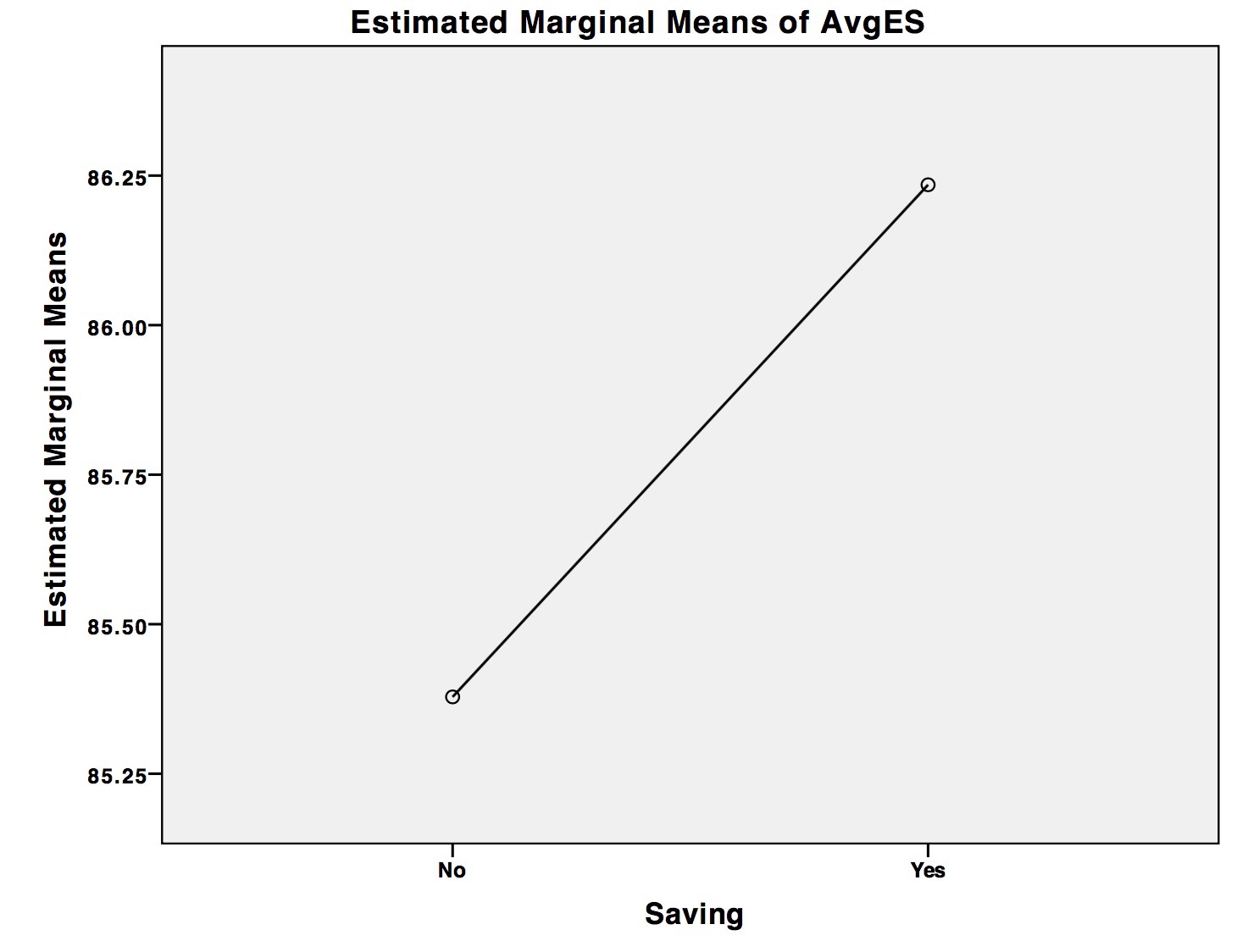

First up, we see a positive and significant overall effect from both of these features in terms of influencing more efficient choices. To be more precise, the presence of the Enervee Score moved the average efficiency of top three choices from an Enervee Score of 84.8 to 86.7 (F=29.5, p=o.00). And the presence of the Energy Savings information moved the average efficiency of top three choices from an Enervee Score of 85.3 to 86.2(F=5.9, p<.05). See Fig. 2.

But here’s the first of two particularly interesting findings from this study.

First, we see no interaction effect between our two Enervee variables (Enervee Score and Energy Savings) and buying context (Context*Score, F=2.3, p>.1; Context*Savings, F=.001, P>.1). In other words, whether we’re buying because we’re planning to remodel or because the machine urgently needs replacing, has no effect on the ability of either the Enervee Score or the Energy Savings to influence more efficient purchases.

In short, the Enervee Score and Energy Savings each show a significant effect on better choices, irrespective of why people are buying.

This is a great result for us, and supports our earlier notion — that by making energy efficiency both real, immediate and personal, even within more compressed decision frames, there’s still an opportunity to drive significantly more efficient outcomes.

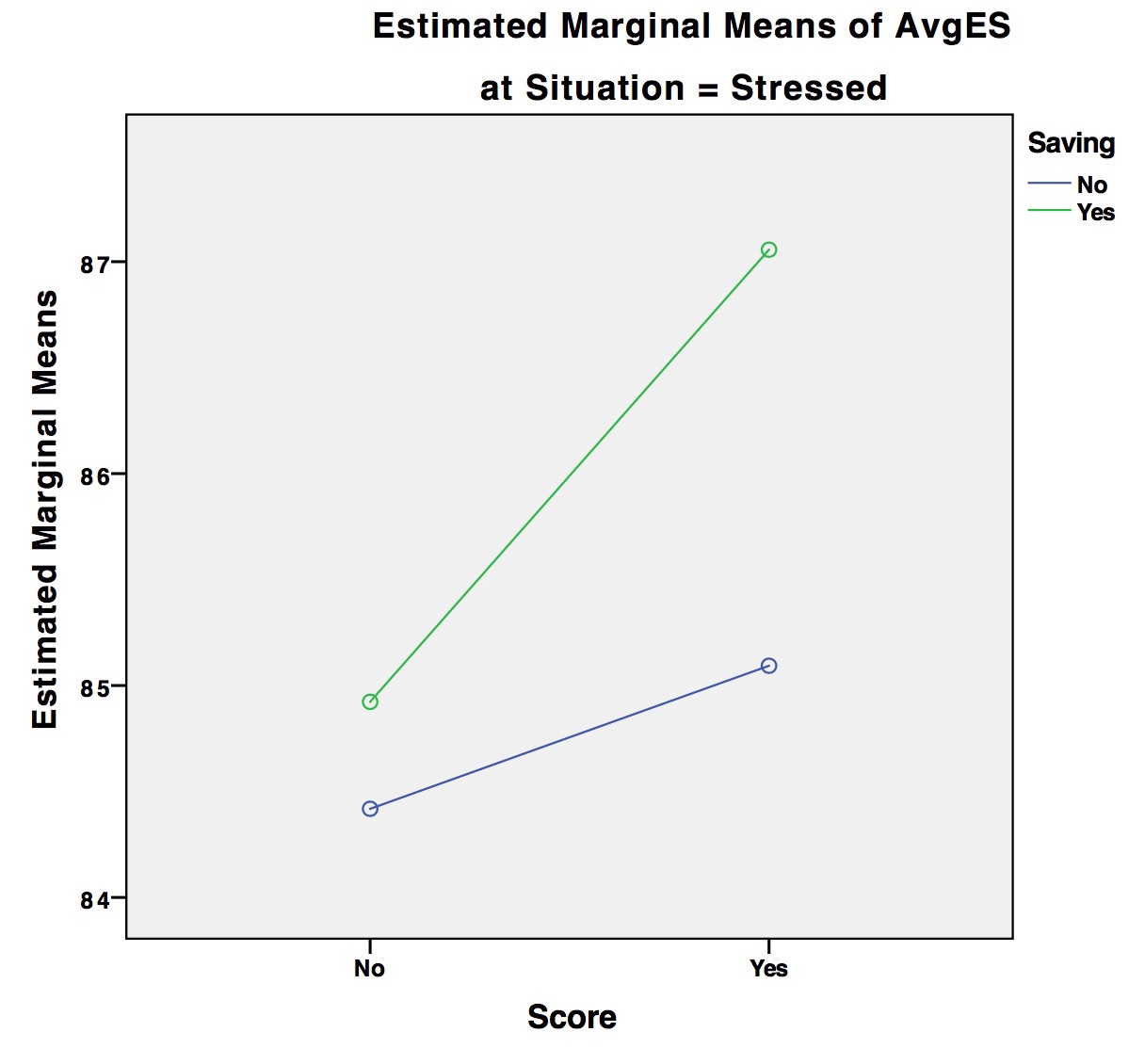

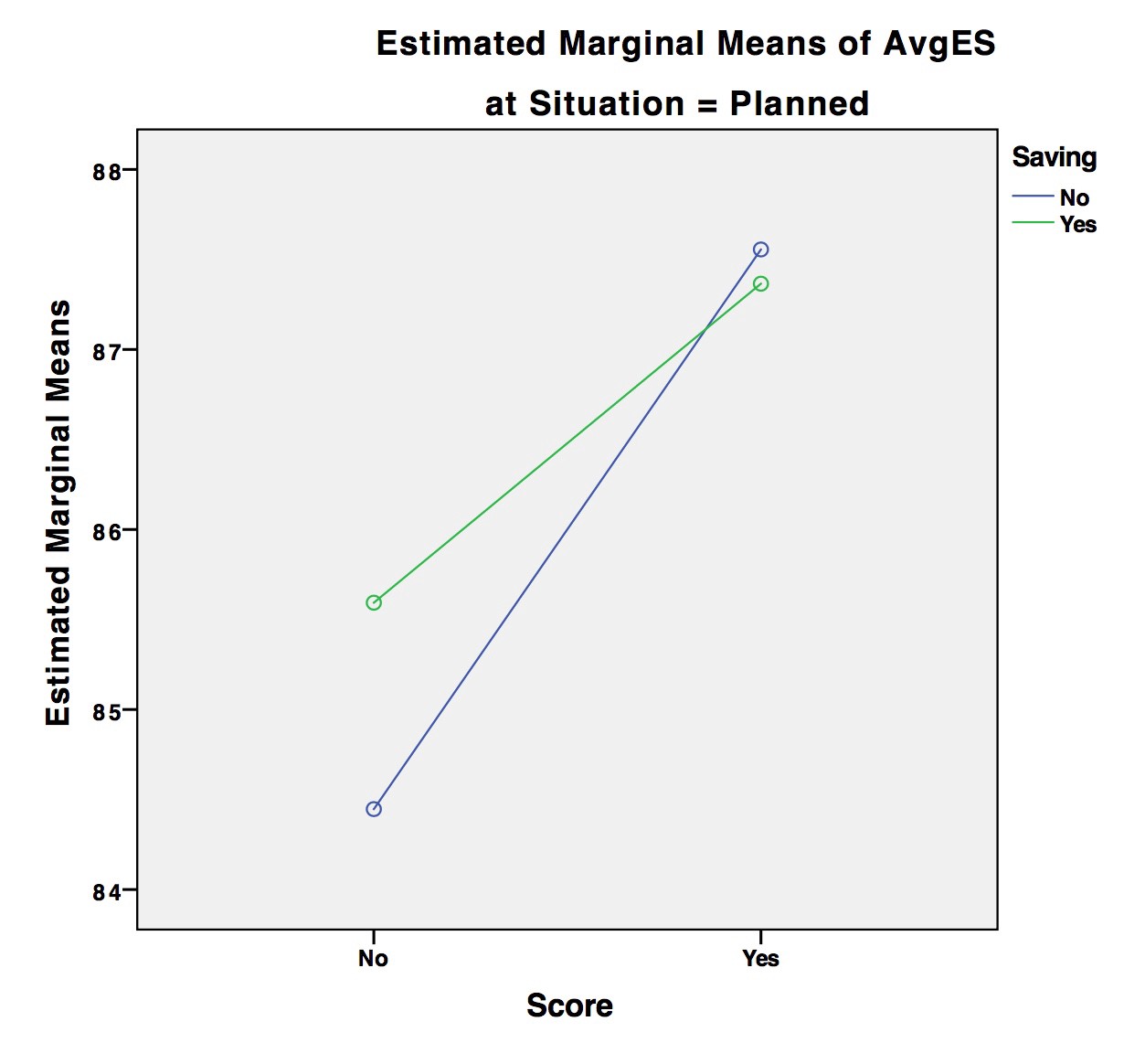

And here’s the second interesting finding from this study — and one we can only see specifically through the design we created (a 3-way factorial design). When we look at the relationship between all three variables (Enervee Score, Energy Savings and Buying Context), we see a 3-way interaction effect (F=3.9, p<.05). This can be a bit heavy going (stay with us) but what this result tells us is that the relationship between the Enervee Score and Energy Savings, in terms of their influence on our choices, changes with the buying context. In other words, how we use these two Enervee features together, depends on why they’re buying. See Fig. 3.

In short, this suggests that within a planned, slow buying context, adding the Energy Savings information to the experience with the Enervee Score already given, adds nothing to the decision outcome. In other words, the Enervee Score is the most influential factor here. But when we’re buying within a distressed, fast buying context, if we add the Energy Savings information to the Enervee Score, we see a considerable step-up in terms of energy efficiency of choices. In other words, presenting both features here is important.

Why might this effect exist? It likely goes back to our opening argument, in terms of energy efficiency and its frustrating propensity to be abstract, impersonal and distant. Whilst the Enervee Score does a good job of disabling these shortcomings in the main (born out by the numerous positive effects we’ve recorded), maybe this isn’t enough to push efficiency over the line for when we’re under pressure to make a quick choice. In other words, when we’re up against it, in terms of replacing a broken appliance, having the Energy Savings to financially quantify the impact of a high Enervee Score choice for us personally, makes all the difference. It’s the final step to keep efficiency in that crucial attribute list, when the decision’s being made.

Practically speaking…

We’re aware that a 3-way interaction effect doesn’t make for easy and immediate conversations around using Enervee Marketplace. Sometimes research lurches off in what looks like an esoteric direction. But that’s really not the case here — we believe this final result adds to an important conversation regarding Marketplace and its ability to nudge us all toward making more efficient choices. Specifically, it adds this:

When we think about segmenting consumers on energy efficient purchasing behavior, we must keep in mind that why we’re buying is an important influence on this behavior.

This context would never be picked up in conventional demographic or even psychographic segmentation techniques. But it’s crucial, because it clearly influences how we make choices, and if we want to improve those choices, then knowing this context is important in refining the intervention to deliver that improvement.

So how might we be able to determine these contexts within the consumer buying journey?

Well, a sizeable advantage to platforms like Marketplace is that we see long engagement times with consumers — more than 50% of their total yearly online time with utilities is typically spent on Marketplace in just one visit. And during this time, Marketplace visitors commit to lots of specific and novel actions (such as how they sort, filter, or look at features for example). Once we know how just a few of these behaviors relate specifically to buying context, we’ll be able to spot, early in the journey, what that context is, and intervene in that journey in such a way as to have a better shot at driving a more efficient purchase.

Which all means — esoteric 3-way interactions or otherwise — outputs like this help us further refine our proposition to nudge more of us into more efficient choices. Which means less energy consumed and a better buying experience. And which could also mean the kids still get to school with clean clothes on Monday.